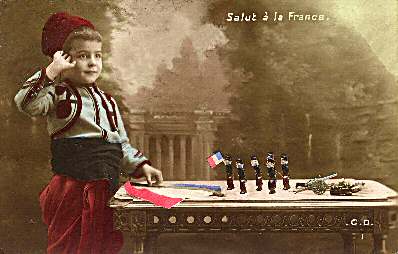

Prompted by the purchase of the the postcard below this tale is a powerful premonition of the Great War.

A small boy, eight years old, sitting crosslegged on the floor of his nursery, surveyed a panorama of his own creation. The worn and faded green of a carpet (which in the circumstances suggested a severe drought) held the bright and serried ranks of two opposing armies. Little lead soldiers, taken that Christmas morning out of their cardboard boxes and painstakingly placed in their present positions by this higher agency, faced each other in attitudes decreed by their particular manufacturers. Some stood to attention, others with arms sloped were on the march, while others still with iced bayonets were prepared to meet a cavalry charge. The boy wore a puzzled frown. Having got his tiny puppets into battle array, how was he to conduct the battle? He regarded his men doubtfully—the eye of destiny itself for a moment baffled. They presented a motley though a colourful appearance. There were Guardsmen in bearskins and scarlet tunics, and Royal Fusiliers in khaki. Ghurkas in turbans and American Indians in warpaint and feathers. United States troops in blue with dark-skinned Cubans in white. French Zouaves in baggy red trousers stood between Italian Bersaglieri in green, and kilted Highlanders. There was even a company, garbed as for a fancy dress ball, in the uniform of the eighteenth century— pike and shako and scarlet coatee. There were lancers with pennants of red and white, and Prussian Uhlans in peaked helmets. A few cannon concealed in a wood, whose trees were the exact replica of those in a “Douanier” Rousseau, and some houses of painted stucco completed the picture.

The boy's idea of battle was not dissociated from death and destruction. But how inflict casualties so that each was decided not by the boy but by fate alone ? How deal them out fairly? “Deal” suggested something. Cards! He ran to find his mother.

She was in the library, a book on her lap, but she was not reading. She was tired; a reaction to the nervous energy and sympathy put into her son's enjoyment of Christmas.

“Mother!” he cried, “can I have a pack of cards?”

“What for?” (Why do parents invariably question and why are children invariably secretive?)

“Oh, nothing, Mother. Can I?”

“Yes, of course” She rose and went to a desk. Opening a drawer, she selected a used pack. “ Here you are, dear.”

“Thank you, Mother.” He was off immediately. His mother followed, but not at once.

In the nursery, presiding over his miniature armies, he soon had the battle under way. Fortune herself determined its course. As one side opened fire the cards were dealt and a card placed before each man fired at.

A face card and he was a casualty. An ace he was killed; a king and he was seriously, perhaps mortally, wounded (a black card following and he died— a red and he recovered). A queen and he was wounded and out of action. A knave and he was wounded but might still go on fighting if he had the pluck. (A card was then dealt to determine this—a diamond or heart and he continued despite his wound and thereby earned a decoration.) Any other than a face card and the man escaped.

So it went. The boy decided attack and counter-attack, but fate determined success or failure. Except where the cannon were concerned from these he fired little pellets, pulling back the spring himself— so many shots a side. Sometimes his governess fired for the enemy, but she was so indifferent a shot that he had to give her up. Once the cannon inflicted considerable damage. The soldiers being in close order, the man hit took the whole line with him in his fall.

After several battles, the boy noticed one young officer who bore a charmed life. Card after card had been dealt him without his even receiving so much as a knave. Scatheless he passed through battle after battle. The boy grew to identify this young subaltern with himself. Not consciously, but vaguely. He became a symbol, a presage, a premonition. When it finally became his turn to be dealt a card the boy became pink with excitement and anticipation. Once, peeping, he expected an ace which happily turned out to be a two.

Not until the late spring, when the family were about to leave New York for England , did the young officer receive his face card— a king. Seriously, perhaps mortally, wounded in a charge at the head of his men!

The little boy sat lost in thought, wishing he could take back the card or hand it to another man. Somehow he could not; he was instinctively honest. And besides, the fact would remain no matter what he did. But the card following—the black card that meant death or the red card that meant life?

He could not bring himself to turn that card up. He put away his toy soldiers, back into their boxes, into the little niches made for each man. He put them all away and never played with them again.

Carroll Carstairs, “A Generation Missing”